The Bible, Hermeneutics, and Deconstruction

here

here

Everybody knows that the Bible has been universally regarded as the most read and most influential book on the planet, having sold over 5 billion copies in nearly 7,000 known languages since its first printing in 1454 in the workshop of Johannes Gutenberg, in Mainz, Germany.

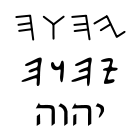

A Greek word biblia (τὰ βιβλία) simply means “books”, alluding to the

collection of 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh,

acronym for Law, Prophets and Writings,

in Hebrew: Torah, Neviim, Ketuvim – תורה

נביאים וכתובים

), called by Christians the Old Testament, which, in addition to the Jewish canon

(grouped into 39 books), also adopt the 27 books of the New Testament

(Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Revelation), as the Catholic Bible

comprises a total of 73 books and the Protestant Bible, 66

(excluding

the so-called Apocrypha).

A

controversial authorship of biblical writings and the great diversity of their

literary genres, contents and meanings corroborate the interesting idea of

a fluid canonicity, influential and constantly revised, sedimented and

consolidated, such as the one that has been developed in comparative literature by

Harold Bloom, situating the Bible, along with the Iliad and the Odyssey by

Homer and Virgil's Aeneid, at the very foundation of a true western canon. The Holy Book of Judaism and

of Christianity, many would consider it hors

concours precisely because of these peculiarities. Since this was the first book that I started reading as a child, I would not hesitate to choose it as one of the

most representative of the human experience of reading, speaking, writing,

understanding, imagining, creating, and networking. An old teacher at Oxford, Donald Drew, used to say that if God didn't exist, we should believe in Shakespeare, such was the latter’s debt to the tragicomic universe and the dramatic imagery of the stories, narratives, and poetic structures of the Bible.

In the same vein, Dante, Cervantes, Milton, Rabelais, and Goethe would only consolidate the formation of a modern canon, as suggested by Bloom. However, instead of discarding marginal authors and readings as Bloom did with the postmodernists and poststructuralists due to a certain School of Resentment, I believe that

the endless conflicts of interpretations, schools of hermeneutics, and

deconstruction associated with different receptions of the Bible by the most diverse

Jewish and Christian traditions point to a rich and complex mosaic of cultural pluralism, encompassing not only traditional and orthodox readings, but

also the most heterodox and antagonistic, including those of the so-called masters of

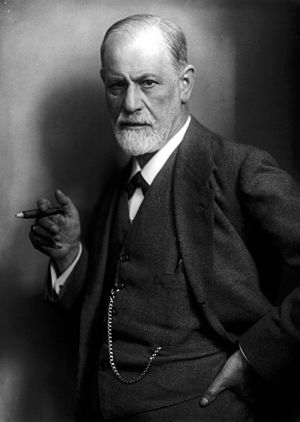

suspicion –Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud— and their contemporary epigones and critics

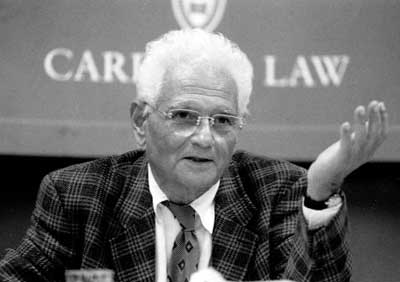

–like Ricoeur, Foucault, Levinas, Derrida – all great readers of the Bible. Not to mention Baruch de Spinoza, who anticipated the hermeneutics of suspicion and the radical prophets of extremity.

Indeed, for Jacques Derrida, deconstruction reveals multiple readings, stratified, coded, and decoded, as it continually reconfigures them according to different orientations – more or less

orthodox, conservative, reformist or radical—of interpretation, as perfomed by Jewish scribes, rabbis, Talmudists, and Kabbalists.

So,

the Hebrew Bible and the Bible of Christian theology conceive of an unfolding

history of creation, redemption, and divine revelation inseparable from the

personal attributes of a transcendent God, but related to human existence,

to the world and to the Other that are immanent to them. We can thus establish a

hermeneutical correlation between biblical-theological revelation and self-understanding in phenomenological-existential terms (of ourselves, our communities and our

traditions). In Jewish theology, one can speak of a written law (Torah) and of an oral law of revelation (Halacha, Talmud, Gemara, Mishnah).

According to Christian theology, one can speak of a general or natural revelation (the

natural law and the laws of nature) and from a special or direct revelation (the Divine Law that God would have communicated to Moses, the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, the salvation, and the mysteries of faith).

Positions

expressing more or less orthodox cultures of Judaism and Christianity deal differently with

the problem of revelation in its presuppositions (miracles, the supernatural, the

divine nature) and its implications (historicity, reception of biblical writings,

the articulation between reason and faith, knowledge and shared beliefs). If deconstruction is a “radical hermeneutics” (John Caputo)

or “the hermeneutics of the death of God” (Mark Taylor), in any case the

deconstruction of onto-theo-logical, essentialist or substantialist concepts

of the God of traditional metaphysics reveals to us a horizon of otherness of the

Whole-Other (Wholly-Other, Tout-Autre,

Ganz Andere) in our encounter with the other, the neighbor, the poor, the

stranger, the orphan, the widow. If the 613 mitzvot (prescriptions) of Judaism must

be taken literally or if they can be synthesized in 10 commandments

(Moses) or 13 guiding principles (Maimonides), the Law of Love or the Golden Rule

translates in the Shema and in the teachings

of Hillel and Jesus the ethics of reciprocity: “Do not do to others what you do not

we want them to do to us” and “do unto others what we want them to do unto us”. A moral universalism erupts within the Torah's own particularism,

originally conceived for the people of Israel in a given historical, ethnolinguistic context. The divine covenant is universal,

as in the story of Noah, whose Seven

Laws boil down to forbidding idolatry (not just of false gods, but

above all pride, self-righteousness, and fundamentalism), murder,

theft, immorality, slander, and mistreatment of animals, which correlated to promoting systems and

laws of justice. Nothing could be more appropriate for today’s liberal democracies that, despite their Judeo-Christian roots, are going through systemic ethical-moral crises since

the surge of the far-right, obscurantism, and religious fanaticism. Ultimately, according to Spinoza, the very Biblical story of redemption, especially the Exodus and the Pesach stories, must be kept in mind as dynamic narratives of liberation that could eventually foster different interpretations of political messianism and spiritual salvation. In effect, Spinoza’s reading of this Hebrew saga turns out to be a radical hermeneutics of a spiritual motif that is eventually deconstructed and secularized from within. As Derrida would later argue, our

obligation of reciprocity and otherness should not be taken as a formal or

categorical imperative, but rather as a token of hope without fulfilled messianism

or as a utopian messianism without a redemptive goal, always to come, à venir.

World Religions - REL 1220 (U Toledo DL)

Modern Philosophy Undergrad Seminar: Immanuel Kant (Spring 2014)

Contemporary Moral Problems - PHIL 2400-902 (U Toledo DL)

Spinoza Ethics Seminar

"O Déficit Normativo do Ethos Democrático Brasileiro"

Spinoza's Critical Hermeneutics of Revelation – Fall 2013

Normativity, Naturalism, and Social Philosophy

(Critical Theory Seminar, Aug-Dec 2012)

Ethics Undergraduate Seminar (Aug-Dec 2012)

Medical Ethics (U Toledo DL)

Toward a Latin American Indigenous Philosophy

Philosophy of Culture

Der Wille zur Macht: Nietzsche-Seminar

Nietzsche e o perspectivismo político

Th. W. Adorno und pop music

Adorno on pop music

Max Horkheimer

Herbert Marcuse (1976 interview)

M. Foucault

M. Heidegger

J.-P. Sartre

Website Fenomenologia

PDF version: "Towards a Phenomenology of Liberation" (APA Newsletter Fall 2010)

Husserl & Heidegger

Liberation Seminar: Latin American Theology and Political Philosophy

Greek Philosophia

Latin Philosophia

Deutsche Philosophie

Philosophie française

|